Tiananmen Square protests of 1989

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

The 1989 Tiananmen Square Protests (Tiananmen Square Massacre or June 4th Massacre or 6/4 incident), were a series of student-led demonstrations held in Tiananmen Square in Beijing, the People's Republic of China, between April 15, 1989 and June 4, 1989. The protest denounced China's economic instability and political corruption and was violently suppressed by the PRC government.

The student's protest started from middle of April 1989, triggered by the death of Hu Yaobang, the stepped down party general secretary. Hu was widely seen as a liberal-minded person and was forced to resign from his position by Deng Xiaoping, an unfair treatment in many people's view, especially among intellectuals.

The protests began on a relative small scale, in the form of mourning for the late Hu Yaobang and demands that the party revise their official view of him. The protests grew larger after news of confrontation between students and police spread - student belief that the Chinese media was distorting the nature of their activities also led to increased support. At Hu's funeral, a large group students gathered at Tiananmen square and requested, but failed, to meet premier Li Peng, widely regarded to be Hu's political rival. Thus students called for a strike in universities in Beijing. On April 26, an editorial in People's Daily, following an internal speech made by Deng Xiaoping, accused the students of plotting turmoil. The statement enraged the students, and on April 27 about 50,000 students went onto the streets of Beijing, ignoring the warning of a crackdown made by authorities and insisted that the government withdraw the statement.

On May 4, approximately 100,000 students and workers peacefully marched in Beijing making demands for free media reform and a formal dialogue between the authorities and student-elected representatives. The government rejected the proposed dialogue, only agreeing to talk to members of appointed student organizations. On May 13, large groups of students occupied Tiananmen square and started a hunger strike, demanding the government withdraw the accusation made in the People's Daily editorial and begin talks with the student representives. Hundreds of students went on hunger strike and were supported by hundreds of thousands of protesting students and residents of Beijing, which lasted for a week.

Although the government declared martial law on May 20, the demonstrations continued. After deliberating among Communist party leaders, the use of military force to resolve the crisis was ordered, and Zhao Ziyang was ousted from political leadership. Soldiers and tanks from the 27th and 38th Armies of the People's Liberation Army were sent to take control of the city. These forces were confronted by Chinese workers and students in the streets of Beijing and the ensuing violence resulted in both civilian and army deaths. The Chinese government acknowledged that a few hundred people died.

Estimates of civilian deaths which resulted vary: 400-800 (New York Times [1]), 1,000 (NSA), and 2,600 (Chinese Red Cross). Student protesters maintained that over 7,000 were killed. Following the violence, the government conducted widespread arrests to suppress the remaining supporters of the movement, limited access for the foreign press and controlled coverage of the events in the mainland Chinese press. The violent suppression of the Tiananmen Square protest caused widespread international condemnation of the PRC government.

Contents |

Background

Since 1978, Deng Xiaoping had led a series of economic and political reforms which had led to the gradual implementation of a market economy (called Socialism with Chinese characteristics) and some political liberalization that relaxed the system set up by Mao Zedong. By early 1989, these economic and political reforms had led two groups of people to become dissatisfied with the government.

The first group included students and intellectuals, who believed that the reforms had not gone far enough, since the economic reforms had only affected farmers and factory workers at that point, - the incomes of intellectuals lagged far behind those who had benefited from reform policies. They were upset at the social and political controls that the Communist Party of China still held. In addition, this group saw the political liberalization that had been undertaken in the name of glasnost by Mikhail Gorbachev. The second group were those, including urban industrial workers, who believed that the reforms had gone too far. The loosening economic controls had begun to cause inflation and unemployment which threatened their livelihood.

In 1989, the primary supporters of the government were rural peasants who had seen their incomes increase considerably during the 1980s as a result of Deng Xiaoping's reforms. However, this support was limited in usefulness because rural peasants were distributed across the countryside. In contrast to urban dwellers who were organized into schools and work units, peasant supporters of the government remained largely unorganized and difficult to mobilize.

The trigger for the protest was the death, due to illness, of the former General Secretary of the Communist Party of China, Hu Yaobang, who was ousted in February 1987. Hu had been seen as a liberal with a common touch, and his ousting in response to student protests in 1987 was widely seen to be unfair. In addition, the death of Hu allowed PRC citizens to express their discontent with his successors without fear of political repression, as it would have been extremely awkward for the Communist Party to ban people from honoring a former General Secretary. Another current in follow-up to the protests was anti-foreigner sentiment, particularly amongst students who believed foreigners were given more rights than native Chinese (see Nanjing Anti-African protests).

In Beijing, a majority of students from the city's numerous colleges and universities participated with support of their instructors and other intellectuals. The students rejected official Communist Party-controlled student associations and set up their own autonomous associations. The students viewed themselves as Chinese patriots, as the heirs of the May Fourth Movement for "science and democracy" of May 4th, 1919. The protests also evoked memories of the Tiananmen Square protests of 1976 which had eventually led to the ousting of the Gang of Four. From its origins as a memorial to Hu Yaobang, who was seen by the students as an advocate of democracy, the students' activity gradually developed over the course of their demonstration from protests against corruption into demands for freedom of the press and an end to/reform of the rule of the PRC by the Communist Party of China and Deng Xiaoping (a Party elder who ruled from behind the scenes). Partially successful attempts were made to reach out and network with students in other cities and with workers.

Although the initial protests were made by students and intellectuals who believed that the Deng Xiaoping reforms had not gone far enough, they soon attracted the support of urban workers who believed that the reforms had gone too far. This occurred because the leaders of the protests focused on the issue of corruption, which united both groups, and because the students were able to invoke Chinese archetypes of the selfless intellectual who spoke truth to power.

Protests escalate

Unlike the Tiananmen protests of 1987, which consisted mainly of students and intellectuals, the protests in 1989 commanded widespread support from the urban workers who were alarmed by growing inflation and corruption. In Beijing, they were supported by a large fraction of people. Similar numbers were found in major cities throughout mainland China, and later in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Chinese communities in North America and Europe.

Protests and strikes began at many colleges in other cities, with many students travelling to Beijing to join the demonstration. Generally, the demonstration at Tiananmen Square was well-ordered, with daily marches of students from various Beijing area colleges displaying their solidarity with the boycott of college classes and with the developing demands of the protest. The students sang "The Internationale," a song about international worker unity through socialism and democracy. The main tactic finally hit upon was a hunger strike by somewhere between several hundred and over a thousand students. This tactic resonated strongly with the Chinese people. While no hunger strikers were observed to become emaciated, a Chinese urban legend persists that some protestors starved to death [2].

Partially successful attempts were made to negotiate with the PRC rulers, who were located nearby in Zhongnanhai, the Communist Party headquarters and leadership compound. Because of the visit of Mikhail Gorbachev in May, foreign media were present in mainland China in large numbers. Their coverage of the protests was extensive and generally favorable towards the protesters, but pessimistic that they would attain their goals. Toward the end of the demonstration, on May 30, a statue of the Goddess of Democracy was erected in the Square and came to symbolize the protest to television viewers worldwide.

The Standing Committee of the Politburo, along with the Party elders (retired but still-influential former officials of the government and Party), were, at first, hopeful that the demonstrations would be short-lived or that cosmetic reforms and investigations would satisfy the protesters. They wished to avoid violence if possible, and relied at first on their far-reaching Party apparatus in attempts to persuade the students to abandon the protest and return to their studies. One barrier to effective action was that the leadership itself supported many of the demands of the students, especially the concern with corruption. However, one large problem was that the protests contained many people with varying agendas, and hence it was unclear with whom the government could negotiate, and what the demands of the protesters were. The confusion and indecision among the protesters was also mirrored by confusion and indecision within the government. The official media mirrored this indecision as headlines in the People's Daily alternated between sympathy with the demonstrators and denouncing them.

The Crackdown

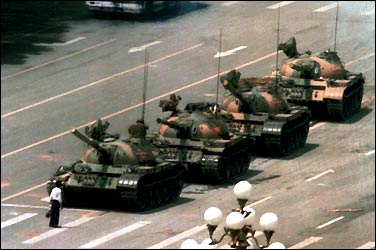

The suppression of the protest was symbolised for many in the West by the famous footage and photographs of a lone protester, taken on June 5, standing in front of a column of advancing tanks, halting their progress. The "tank man" continued to stand defiantly in front of the tanks for half an hour before members of the Public Security Bureau (PSB) - China's secret police - pulled him away. Despite efforts, to this day Western media sources are unable to identify that solitary figure. Time Magazine dubbed him The Unknown Rebel and later named him one of the "100 Most Influential People of the 20th Century". Shortly after the incident, British tabloid the Sunday Express named him as Wang Weilin, a 19-year-old student; however, the veracity of this claim is dubious. What has happened to Wang following the demonstration is equally obscure. In a speech to the President's Club in 1999, Bruce Herschensohn — former deputy special assistant to President of the United States Richard Nixon and a member of the President Ronald Reagan transition team — reported that he was executed 14 days later; other sources say he was killed by a firing squad a few months after the Tiananmen Square protests. In Red China Blues: My Long March from Mao to Now, Jan Wong writes that the man is still alive in hiding in mainland China.

Within the Square itself, there was apparently a debate between those including Han Dongfang, who wished to withdraw peacefully, and those including Chai Ling, who wished to stand within the square at the risk of possibly creating a bloodbath. Those in favor of withdrawal won, and the protesters left the square. The PRC government has claimed that no one was killed in the square itself, a fact that by the accounts of those who were actually in the Square appears to be technically true, but misleading in that it does not account for the casualties in the approaches to the square. The number of dead and wounded remains a state secret. An unnamed Chinese Red Cross official at the time reported that 2,600 people were killed, and 30,000 injured. Two days later, Yuan Mu, the speaker of the State Council, estimated that 300 soldiers and citizens died, as well as 5,000 soldiers and 2,000 citizens injured, 400 soldiers lost contact. According to universities, 23 students died; nobody was crushed. Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and State Council later co-claimed that tens of PLA soldiers died and more injured. The Preparatory Committee of Autonomous Associations of Tsinghua University claimed that 4,000 died and 30,000 injured. Chen Xitong, Beijing mayor, reported at 26 days after the event that 36 students, tens of soldiers died amounting to a total of 200 dead, 3,000 civilians and 6,000 soldiers injured. [3]. Foreign reporters that witnessed the incident have claimed that at least 3,000 people had died. Some lists of the casualties were created from underground sources with numbers as high as 5,000. [4] However, it is important to note that NSA documents declassified in 1999 show that their intelligence gives an estimate of 180-500 killed. Thus the various PRC government estimates are in agreement with the official US government estimate.

Attempts were made during and after the suppression of the demonstration to arrest and prosecute the student leaders of the Chinese democracy movement, notably Wang Dan, Chai Ling and Wuer Kaixi. Wang Dan was caught and convicted and sent to prison, then allowed to emigrate to the United States on the grounds of medical parole. Wuer Kaixi escaped to Taiwan. He has then married and holds a job as a political commentator on National Taiwan TV. Chai Ling escaped to France and then the United States. Within the leadership, Zhao Ziyang, who had opposed martial law, was removed from power, and Jiang Zemin, the then Mayor of Shanghai, who was not involved at all in this event was elevated to become PRC's President. Members of the government eventually prepared a white paper on the incident, which was eventually published in the West in January 2001 as the Tiananmen Papers, which gives the government's viewpoint on the protests and was provided by an anonymous source purportedly within the PRC government. The papers include a quote by Communist Party elder Wang Zhen which alludes to the government's eventual response to the situation.

After the crackdown in Beijing on June 4, protests continued in much of mainland China for a number of days. The PRC government was able to end these protests outside of Beijing, without significant loss of life.

Two CCTV presenters who reported news in the "News Network" program at June 4 were fired soon after the event. Wu Xiaoyong (吴晓镛), the son of a Communist Party of China Central Committee member, former PRC foreign minister and vice premier Wu Xueqian, were removed from the English Program Department of Chinese Radio International.

Aftermath

The Tiananmen Protests seriously damaged the reputation of the PRC in the West. Much of the impact of the protests in the West was due to the fact that western media had been invited to cover the visit of Mikhail Gorbachev in May, and therefore were able to cover some of the government crackdown live through networks such as the BBC and CNN. Coverage was aided by the fact that there were sharp conflicts within the government itself about what to do about the protests, with the result that the broadcasting was not immediately stopped.

CNN was eventually ordered to terminate broadcasts from the city during the crackdown, and although the networks attempted to defy these orders and were able to cover the protests via telephone, the government was able to shut down the satellite links.

Images of the protests along with the collapse of Communism that was occurring at the same time in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe would strongly shape Western views and policy toward the PRC throughout the 1990s and into the 21st century. There was considerable sympathy for the student protests among Chinese students in the West, and almost immediately, both the United States and the European Union announced an arms embargo, and the image throughout the 1980s of a China which was reforming and a valuable counterweight and ally against the Soviet Union was replaced by that of a repressive authoritarian regime. The Tiananmen protests were frequently invoked to argue against trade liberalization with mainland China and by the blue team as evidence that the PRC government was an aggressive threat to world peace and United States interests. Interestingly, western media ignores the fact that the students were singing The Internationale.

Among overseas Chinese students, the Tiananmen Square protests triggered the formation of Internet news services such as the China News Digest. In the aftermath of Tiananmen, organizations such as the China Alliance for Democracy and the Independent Federation of Chinese Students and Scholars were formed, although these organizations would have limited political impact beyond the mid-1990s.

In Hong Kong, the Tiananmen square protests led to fears that the PRC would not honor its commitments under one country, two systems in the impending handover in 1997. One consequence of this was that the new governor Chris Patten attempted to expand the franchise for the Legislative Council of Hong Kong which led to friction with the PRC. There have been large candlelight vigils in Hong Kong every year since 1989 and these vigils have continued following the transfer of power to the PRC in 1997.

The Tiananmen square protests dampened the growing concept of political liberalization that was popular in the late 1980s; as a result, many democratic reforms that took place during the 1980s were rolled back. Although there has been some increase in personal freedom since then, discussions on structural changes to the PRC government and the role of the Chinese Communist Party remain largely taboo.

Nevertheless, despite early expectations in the West that PRC government would soon collapse and be replaced by the Chinese democracy movement, by the early 21st century the Communist Party of China remained in firm control of the People's Republic of China, and the student movement which started at Tiananmen was in complete disarray.

One reason for this was that the Tiananmen protests did not mark the end of economic reform. Granted, in the immediate aftermath of the protests, conservatives within the Communist Party attempted to curtail some of the free market reforms that had been undertaken as part of Chinese economic reform, and reinstitute administrative controls over the economy. However, these efforts met with stiff resistance from provincial governors and broke down completely in the early 1990s as a result of the collapse of the Soviet Union and Deng Xiaoping's trip to the south. The continuance of economic reform led to economic growth in the 1990s, which allowed the government to regain much of the support that it had lost in 1989. In addition, none of the current PRC leadership played any active role in the decision to move against the demonstrators, and one major leadership figure Premier Wen Jiabao was an aide to Zhao Ziyang and accompanied him to meet the demonstrators.

In addition, the student leaders at Tiananmen were unable to produce a coherent movement or ideology that would last past the mid-1990s. Many of the student leaders came from relatively well off sectors of society and were seen as out of touch with common people. Furthermore, many of the organizations which were started in the aftermath of Tiananmen soon fell apart due to personal infighting. In addition, several overseas democracy activists were supportive of limiting trade with mainland China which significantly decreased their popularity both within China and among the overseas Chinese community.

Among intellectuals in mainland China, the impact of the Tiananmen protests appears to have created something of a generation gap. Intellectuals who were in their 20s at the time of the protests tend to be far less supportive of the PRC government than younger students who were born after the start of the Deng Xiaoping reforms. Growing up with little memory of Tiananmen and no memory of the Cultural Revolution, but with a full appreciation of the rising prosperity and international influence of the PRC as well as the difficulties that Russia has had since the end of the Cold War, many Chinese no longer consider immediate political liberalization to be wise, preferring to see slow stepwise democratization instead. Rather, many young Chinese, in view of PRC's rise, are now more concerned with economic development, nationalism, the restoration of China's prestige in international affairs, and perceived governmental weakness on issues like the Political status of Taiwan or the Diaoyu Islands dispute with Japan.

Among urban industrial workers, the continuation of market reforms in the 1990s brought with it higher standards of living as well as increased economic uncertainty. Protests by urban industrial workers over issues such as unpaid wages and local corruption remain frequent with estimates of several thousand of these protests occurring each year. The Communist Party of China appears unwilling to suffer the negative attention of suppressing these protests provided that protests remain directed at a local issue and do not call for deeper reform and do not involve coordination with other workers. In a reversal of the situation in 1989, the center of discontent in mainland China appears to be in rural areas, which have seen incomes stagnate in the 1990s and have not been involved in much of the economic boom of that decade. However, just as the lack of organization and the distribution of peasants prevented them from becoming mobilized in support of the government in 1989, these factors also inhibit mobilization against the government in the early 21st century.

The Present

The topic is still a political taboo in mainland China, where any discussion on it is regarded as inappropriate or risky. The only media coverage is about the Chinese Communist Party's view: that it was a determined action to ensure stability. Every year, there are demontrations in Hong Kong against the decision of the party in 1989.

However, petition letters over the incident have emerged from time to time, notably from Dr. Jiang Yanyong and Tiananmen Mothers, an organization founded by a mother of a killed victim during 1989. Tiananmen Square is tightly patrolled on the anniversary of June 4 to prevent any commemoration.

After the PRC Central Government reshuffle in 2004, several cabinet members mentioned Tiananmen. In October 2004, during President Hu Jintao's visit to France, he reiterated that "the government took determined action to calm the political storm of 1989, and enabled China to enjoy a stable development". He insisted that the government's view on the incident would not change.

In March 2004, Premier Wen Jiabao said in a press conference that during the 1990s there was a severe political storm in the PRC, amid the breakdown of the Soviet Union and radical changes in Eastern Europe. He stated that the Communist Central Committee successfully stablilised the open-door policy and protected the "Career of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics".

US - EU arms embargo

The U.S. and European Union (EU) embargo on weapons sales to the PRC, put in place as result of the violent suppression of the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests, still remains in place 16 years later. The PRC has been calling for a lift of the ban for many years and has had a varying amount of support from members of the EU Council. In early 2004, France spearheaded the movement within the EU to lift the ban. German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder publicly added his voice to that of French President Jacques Chirac to have the embargo lifted.

The arms embargo was discussed at a PRC-EU summit in the Netherlands on 7th-9th December, 2004. In the run up to the summit, the PRC had attempted to increase pressure on the EU Council to lift the ban by warning that the ban could hurt PRC-EU relations. PRC Vice Foreign Minister Zhang Yesui called the ban "outdated", and he told reporters, "If the ban is maintained, bilateral relations will definitely be affected." In the end, the EU Council did not lift the ban. EU spokeswoman Françoise le Bail said there were still concerns about PRC's commitment to human rights. But at the time, the EU did state its commitment to work towards lifting the ban. Bernard Bot, Foreign Minister of the Netherlands, which holds the EU’s rotating presidency, said, "We are working assiduously but... the time is not right to lift the embargo." Following the summit, the EU Council confirmed that it had the political will to continue to work towards lifting the embargo. PRC Premier Wen Jiabao said after the meeting that the embargo did not reflect the partnership between the PRC and the EU.

The PRC continued to press for the embargo to be lifted, and some member states began to drop their opposition. Jacques Chirac pledged to have the ban lifted by mid-2005. However, the Taiwan anti-secession law passed in Beijing (March 2005) increased cross-strait tensions and damaged attempts to lift the ban, several EU Council members changing their minds. Members of the U.S. Congress had also proposed restrictions on the transfer of military technology to the EU if they lifted the ban. Thus the EU Council failed to reach a consensus and although France and Germany pushed to have the embargo lifted, no decision was agreed upon in subsequent meetings.

Britain took charge of the EU Presidency in the summer of 2005, making the lifting of the embargo all but impossible for the duration of the term. Britain had always had some reservations on lifting the ban and wishes to put it to one side, rather than sour EU-US relations further. Perhaps more importantly, the failure of the European Constitution and the ensuing row over the European Budget and Common Agricultural Policy has superseded the matter of the embargo in importance. Britain will use its presidency to push for wholescale reform of the EU, so the lifting of the ban will become even more unlikely. The election of a new European Commission President, Jose Manuel Barroso, has also made a lifting of the ban more difficult. At a meeting with Chinese leaders in mid-July 2005, he said that China's poor record on human rights would slow any changes to the EU's ban on arms sales to China. [5]

Political will may be changing in countries that are more in favour of lifting the embargo. Gerhard Schröder lost a Federal election in September 2005. His opponent, Angela Merkel, is strongly against lifting the ban and narrowly won - though she may not be able to form a government, thus requiring fresh elections. Other opposition leaders are against lifting the ban. Jacques Chirac will find it difficult to remain president in 2007 - he may not even be a successful candidate, due to losing the French vote over the European Constitution. Nicolas Sarkozy is a strong contender for the French presidency and is not as in favour of lifting the ban as Chirac is.

In addition, the European Parliament has consistently opposed the lifting of the arms embargo to the PRC. Though its agreement is not necessary in lifting the ban, many argue it reflects the will of the European people better as it is the only directly elected European body - the EU Council is appointed by member states.

See also

References

- The new Emperors" China in the Era of Mao and Deng, Harrison E. Salisbury, New York, 1992, Avon Books, ISBN 0380720256.

- The Tiananmen Papers, The Chinese Leadership's Decision to Use Force Against their Own People—In their Own Words, Compiled by Zhang Liang, Edited by Andrew J. Nathan and Perry Link, with an afterword by Orville Schell, PublicAffairs, New York, 2001, hardback, 514 pages, ISBN 1-58648-012-X An extensive review and synopis of The Tiananmen papers in the journal Foreign Affairs may be found at Review and synopsis in the journal Foreign Affairs.

- June Fourth: The True Story, Tian'anmen Papers/Zhongguo Liusi Zhenxiang Volumes 1–2 (Chinese edition), Zhang Liang, ISBN 9628744364

- Red China Blues: My Long March from Mao to Now, Jan Wong, Doubleday, 1997, trade paperback, 416 pages, ISBN 0385482329 (Contains, besides extensive autobiographical material, an eyewitness account of the Tiananmen crackdown and the basis for an estimate of the number of casualties.)

External links

- The U.S. "Tiananmen Papers"

- CIA's War Against China

- Graham Earnshaw's eye witness account of events on the night of June 4

- Journal of Foreign Affairs: The Tiananmen Papers

- TIANANMEN SQUARE MASSACRE 1989—Comprehensive Link List

- Frontline: The Gate of Heavenly Peace

- A documentary film

- The Myth of Tiananmen And the Price of a Passive Press, by Jay Mathews, Columbia Journalism Review

- The Tiananmen Square Confrontation, Alternative Insight

- State Department declassified documents

- TIME: The Unknown Rebel

- Global Tiananmen Vigil - Remember the victims of the June 4 massacre by lighting a candle in your window

- Eyewitness account of the massacre

- Report of US government's involvement in TAM protest training provided by Pentagon's Defense Intelligence Agency operative Col. Robert Helvey